Climate change is already causing all sorts of problems on Earth, but soon it will be making a mess in orbit around the planet too, a new study finds.

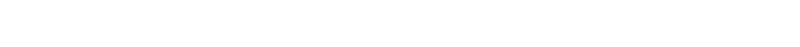

This satellite image from Feb. 25 shows three cyclones, from left, Alfred, Seru and Rae east of Australia in the South Pacific.

MIT researchers calculated that as global warming caused by the burning of coal, oil and gas continues, it may reduce the available space for satellites in low Earth orbit by anywhere from one-third to 82% by the end of the century, depending on how much carbon pollution is spewed. That's because space will become more littered with debris as climate change lessens nature's way of cleaning it up.

Part of the greenhouse effect that warms the air near Earth's surface also cools the upper parts of the atmosphere where space starts and satellites zip around in low orbit, That cooling also makes the upper atmosphere less dense, which reduces the drag on the millions of pieces of human-made debris and satellites.

People are also reading…

That drag pulls space junk down to Earth, burning up on the way. But a cooler and less dense upper atmosphere means less space cleaning itself. That means that space gets more crowded, according to a new study in Nature Sustainability.

ŌĆ£We rely on the atmosphere to clean up our debris. ThereŌĆÖs no other way to remove debris,ŌĆØ said study lead author Will Parker, an astrodynamics researcher at MIT. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs trash. ItŌĆÖs garbage. And there are millions of pieces of it.ŌĆØ

Circling Earth are millions of pieces of debris about one-ninth of an inch and larger ŌĆö the width of two stacked pennies ŌĆö and those collide with the energy of a bullet. There are tens of thousands of plum-sized pieces of space junk that hit with the power of a crashing bus, according to The Aerospace Corp., which monitors orbital debris. That junk includes results of old space crashes and parts of rockets with most of it too small to be tracked.

There are 11,905 satellites circling Earth ŌĆö 7,356 in low orbit ŌĆö according to the tracking website Orbiting Now. Satellites are critical for communications, navigation, weather forecasting and monitoring environmental and national security issues.

A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket with a SXM-9 digital, audio radio satellite payload, lifts off from pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center on Dec. 5, 2024, in Cape Canaveral, Fla.

ŌĆ£There used to be this mantra that space is big. And so we can we can sort of not necessarily be good stewards of the environment because the environment is basically unlimited,ŌĆØ Parker said.

But a 2009 crash of two satellites created thousands of pieces of space junk. Also, NASA measurements are showing a measurable reduction of drag, so scientists now realize that that ŌĆ£the climate change component is really important,ŌĆØ Parker said.

The density at 250 miles above Earth is decreasing by about 2% a decade and is likely to intensify as society pumps more greenhouse gas into the atmosphere, said Ingrid Cnossen, a space weather scientist at the British Antarctic Survey who was not part of the research.

Cnossen said in an email that the new study makes ŌĆ£perfect senseŌĆØ and is why scientists have to be aware of climate change's orbital effects ŌĆ£so that appropriate measures can be taken to ensure its long-term sustainability.ŌĆØ

Is the US becoming uninsurable? How climate change affects insurance costs

Is the US becoming uninsurable? How climate change affects insurance costs

As Southern California still reels from January's catastrophic wildfires, the economic damage has surged to $250 billion, far exceeding initial estimates. But that figure doesn't account for damage incurred by residents whose homes and businesses were reduced to rubble and ash.

The Palisades and Eaton fires alone will result in up to to homeowners and businesses, according to data analytics firm CoreLogic. Of course, that only applies to residents who had insurance in the first place.

In the wake of an extreme weather event, residents typically can rely on insurance claims to repair damaged property ŌĆöbut the increasing frequency and severity of fires, storms, floods, and other occurrences complicate coverage.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in 2023 documented across the U.S., a number that outpaced any prior year on record. Climate change is the main culprit fueling these disasters' increasing frequency and intensity. By September 2023, NOAA reported that the U.S. had already racked up a staggering for that year.

Insurance companies have responded with higher rates to cover costs, culminating in overall higher insurance fees for customers. In June, the Bipartisan Policy Center reported that every quarter since the end of 2017. And car insurance isn't faring any better, either: According to the Washington Post, blizzards, tornadoes, and hailstorms led to a from 2013 to 2023, and hurricanes are responsible for an 88% jump in Florida over the same period.

┬Āused data from to analyze the rising number of billion-dollar disasters and their implications for the insurance marketplace in the U.S.

Some insurers have begun leaving states altogether to ensure profit margins, particularly in coastal areas. Notably, Allstate and State Farm halted new policy sales in 2023 for property and casualty coverage in California due to wildfire costs. Many insurers have abandoned Louisiana and Florida residents as hurricane risk intensifies.

Annual home insurance rates average $2,258 as of February 2025ŌĆöa slight dip from last year. Costs vary widely based on a home's size, age, and location. Nebraska, Florida, and Oklahoma have the highest rates in the nation.

Severe storms cause the most damage nationally each year

Droughts, storms, and floods were nearly unrelenting throughout 2023. In August, Hurricane Idalia brought storm surge, heavy rains, and flooding to Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas, causing $3.5 billion in damages. 2024 didn't offer much of a break, either. The year began with tornadoes and high winds across the entire East Coast, racking up $1.8 billion in damages, and ended with back-to-back catastrophic hurricanes, Helene and Milton. Together, they caused an estimated $300 billion in damages and killed 250 people in Florida and other southeastern states.

With severe weather disasters becoming more common, the market for insurance has become more limitedŌĆöespecially in disaster-prone states. In Florida and California, for instance, some big-name insurers have stopped providing services altogether. To counter this, Florida implemented the Hurricane Catastrophe Fund and Citizens Property Insurance Corporation, both of which subsidize home insurance.

California, on the other hand, regulates insurer rates by only allowing them to evaluate based on the past 20 years, not just the current conditions. Both methods are imperfect: Florida's subsidy funds are draining quickly, and many insurers refuse to operate in California.

It's important to note that insurance alone is just treating the symptom of a larger issue: In addition to reevaluating home and auto insurance policies, states need to examine how they brace forŌĆöand recover fromŌĆönatural disasters overall. As storms grow and insurance vanishes, they can't afford not to.

A mutually beneficial option might be for insurers and clients to engage in more transparent negotiations. In wildfire-riddled Oregon, for example, new legislation is attempting to encourage insurers to work with citizens to identify and increase coverage for mitigation measures.

Story editing by Nicole Caldwell and Alizah Salario. Additional editing by Kelly Glass and Elisa Huang. Copy editing by Tim Bruns and Kristen Wegrzyn.

originally appeared on and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.